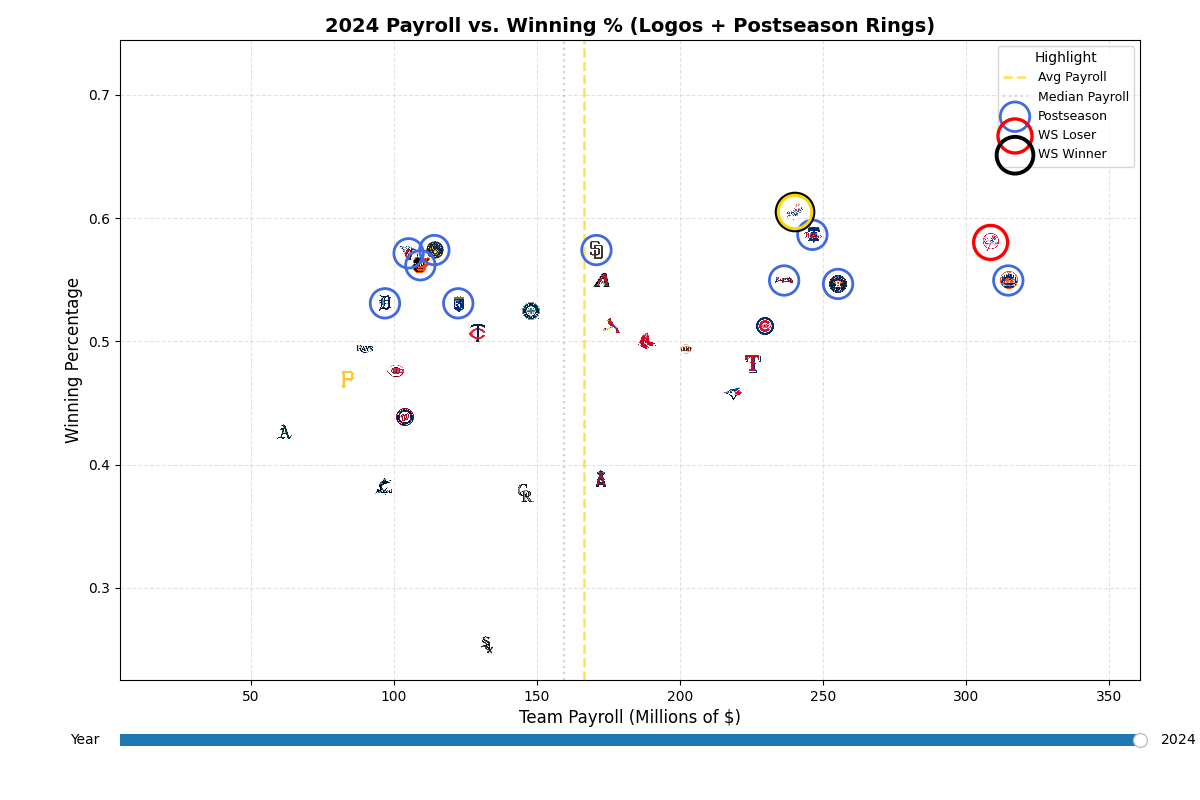

The Los Angeles Dodgers won the World Series last week with a league-leading ~$350 million payroll. The New York Mets missed the playoffs with with a payroll around ~$341 million. Money doesn't buy World Series championships—it can't; only one team wins the World Series every year while nine teams exceeded the Competitive Balance Tax (CBT) threshold in 2024. This is a "luxury tax" incurred by teams with player salaries exceeding a predetermined amount; $241 million was the number in 2025. Those pointing to the Dodgers saying "they're buying championships" are wrong; you can't buy championships. But those pointing to the Mets saying "money doesn't buy championships" should understand that it really helps.

This data project uses christophertreasure's data set on Kaggle, which is sourced from Spotrac and includes all team payroll data, wins, losses, and postseason appearances from 2011-2024. I used Python to analyze the correlation between wins and payroll. The moderate correlation wasn't shocking. Spending hundreds of millions more than other teams confers a moderate advantage. It's an inherent notion to those of us who've grown up watching the sport. But more recently a different trend has evolved. It's of note for fans of franchises with spending-averse owners to to realize just how much hope their owners are asking them to buy without paying for it themselves.

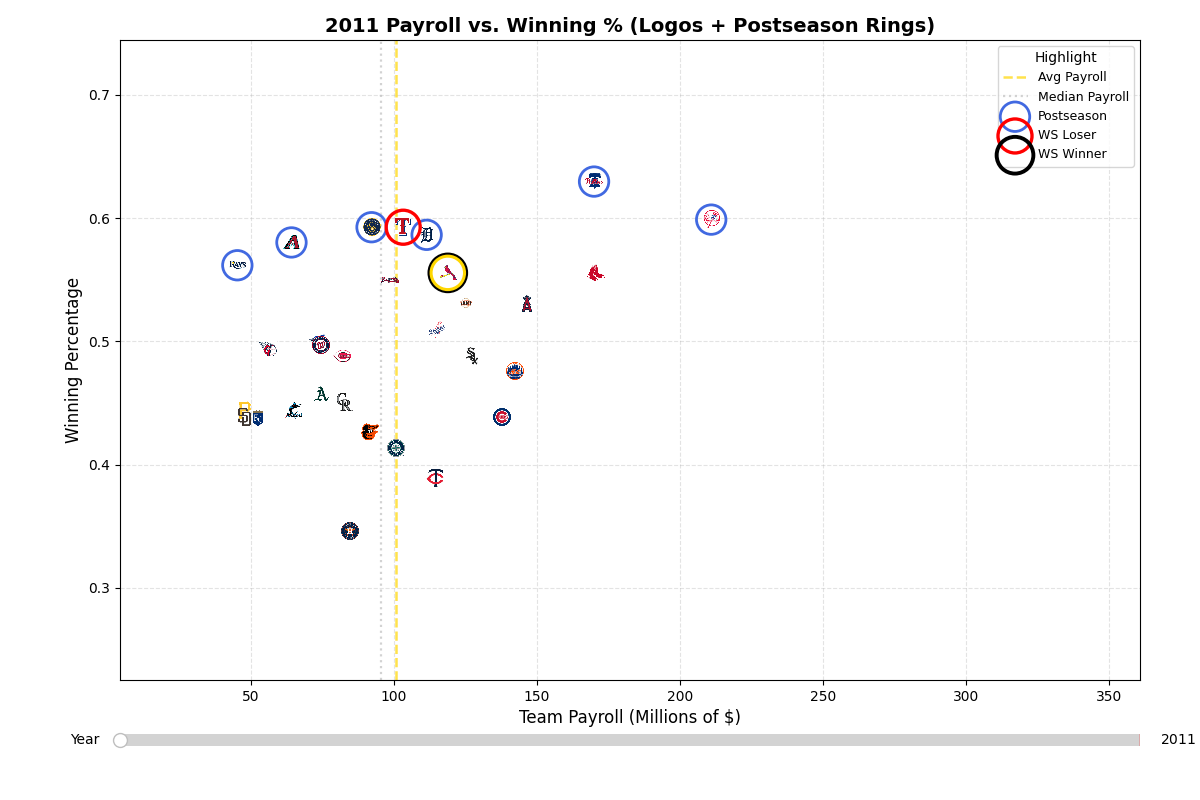

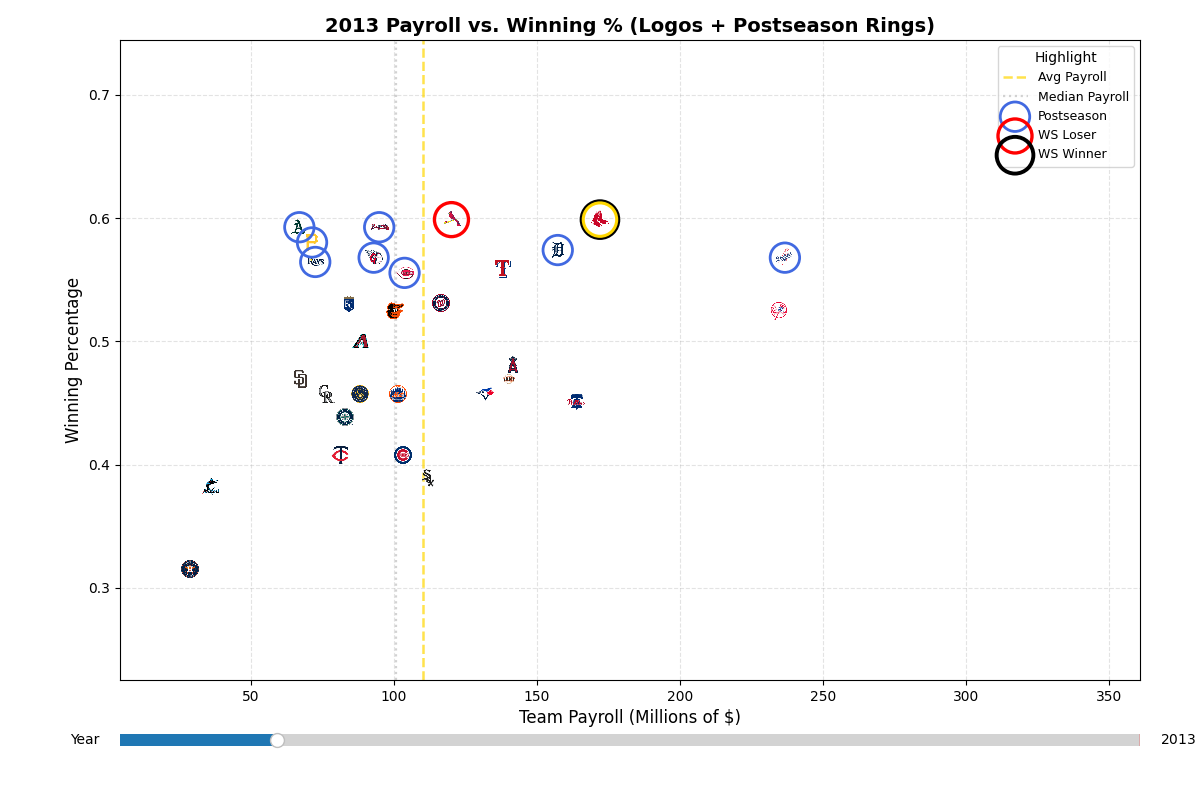

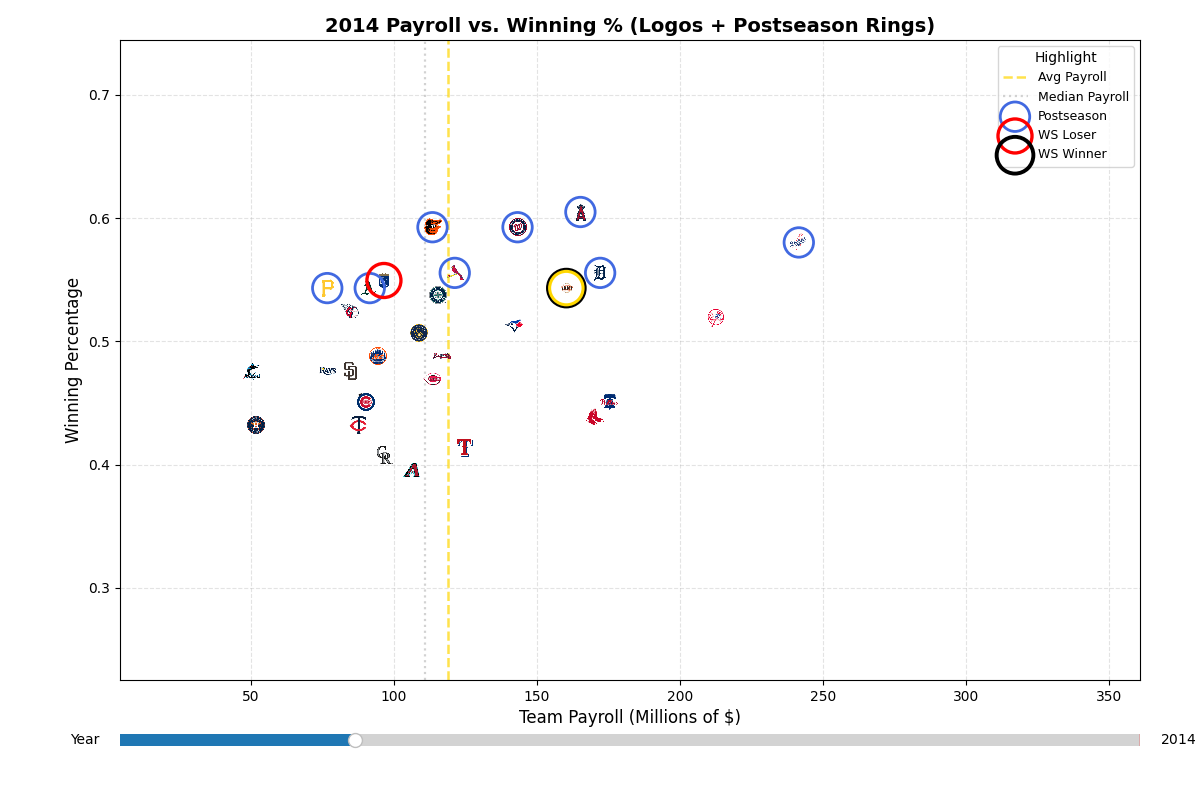

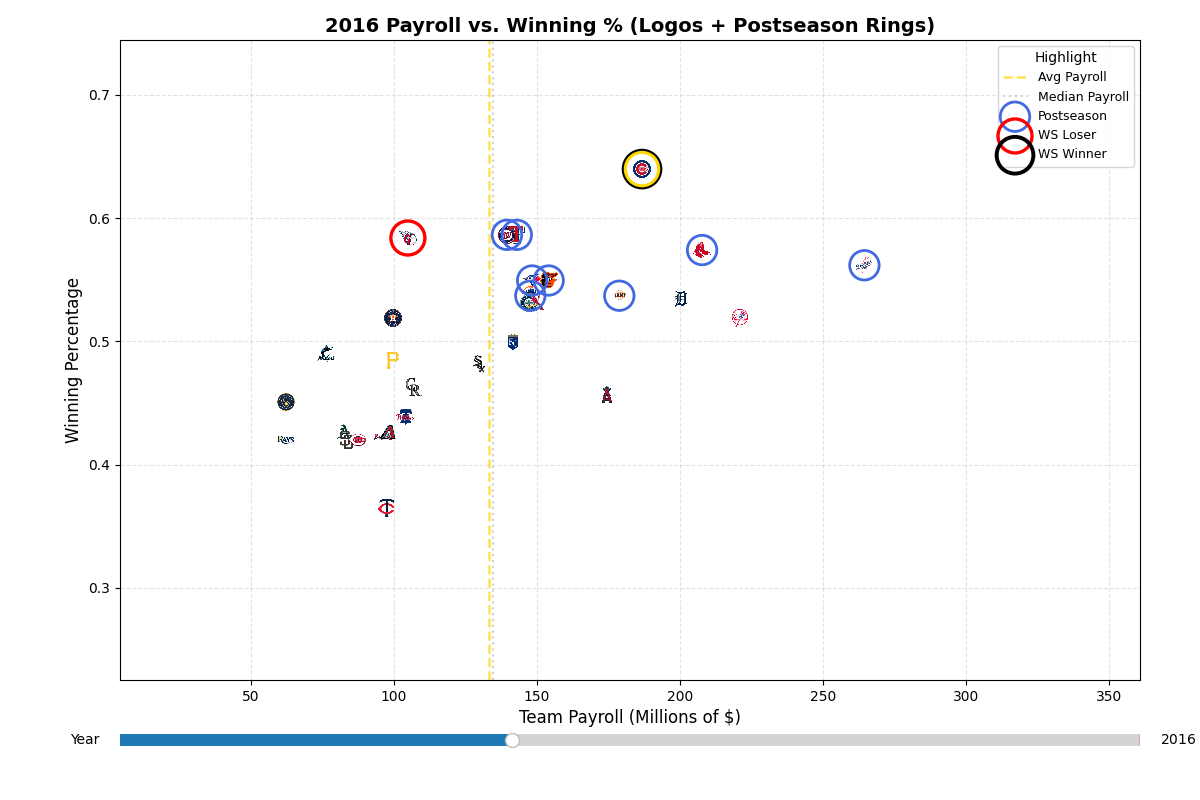

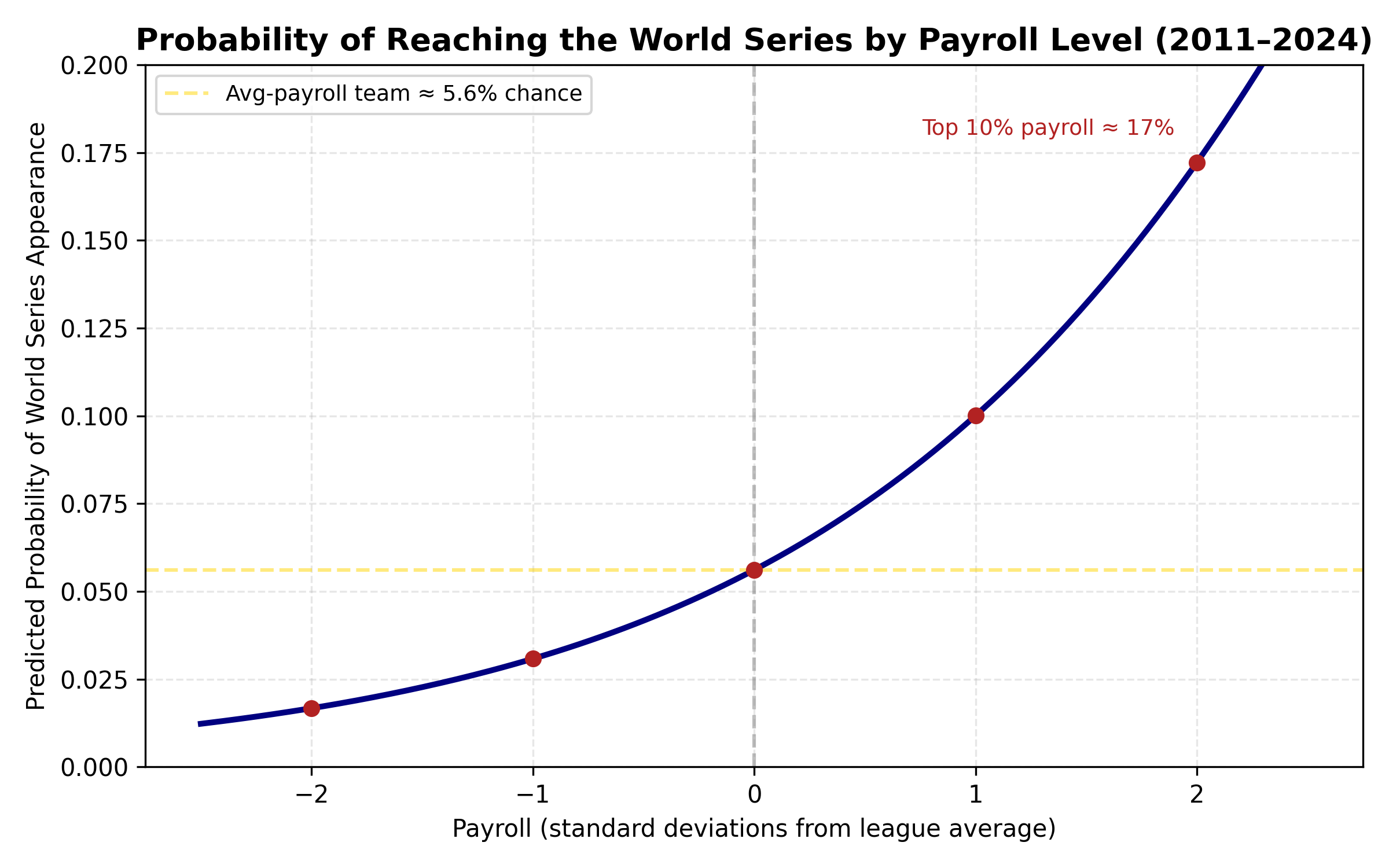

From 2011 to 2024, payroll and winning percentage carried a correlation coefficient of roughly .4; in that same period, each standard-deviation increase in payroll nearly doubled a team’s odds of reaching the World Series.

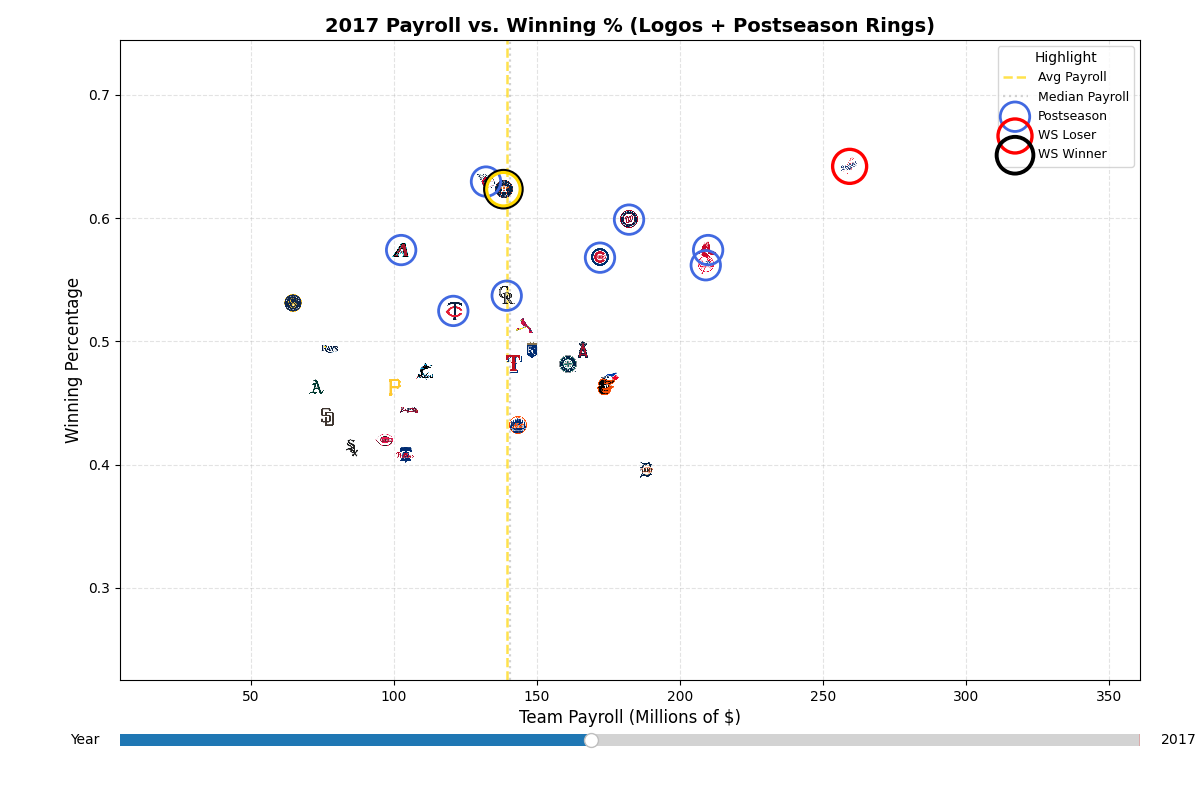

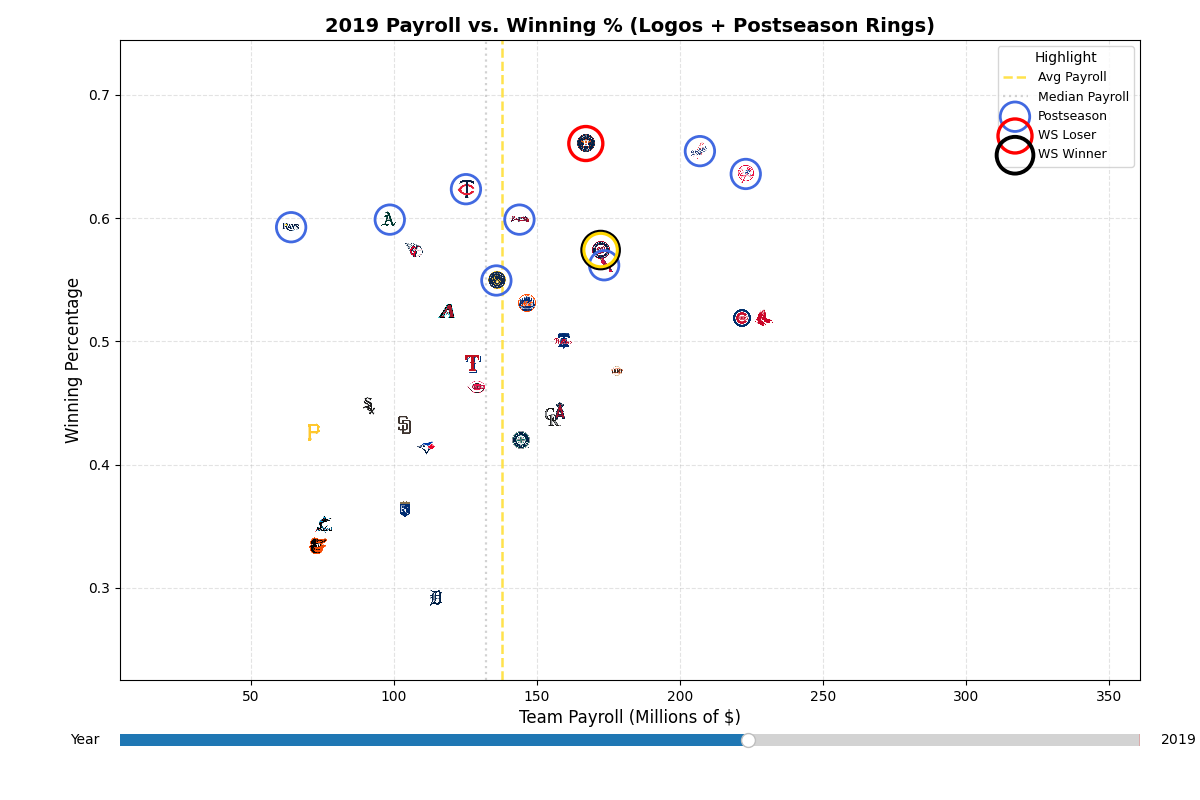

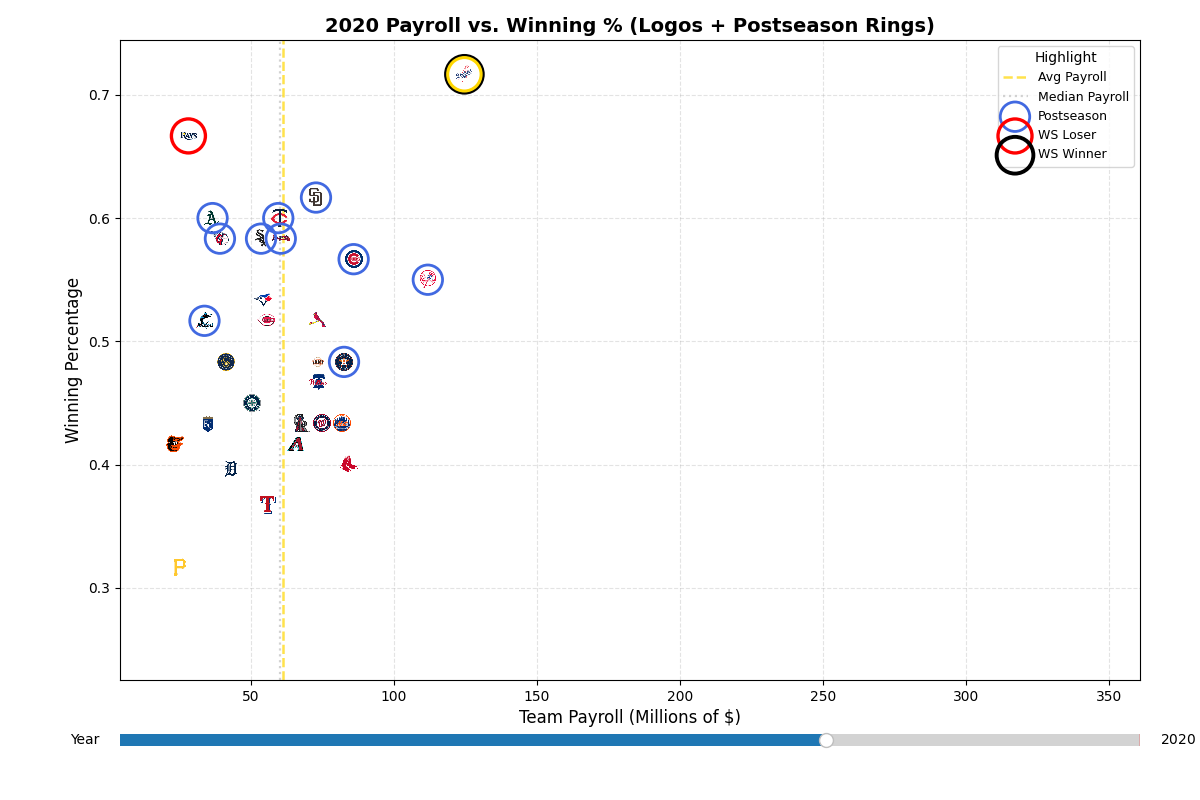

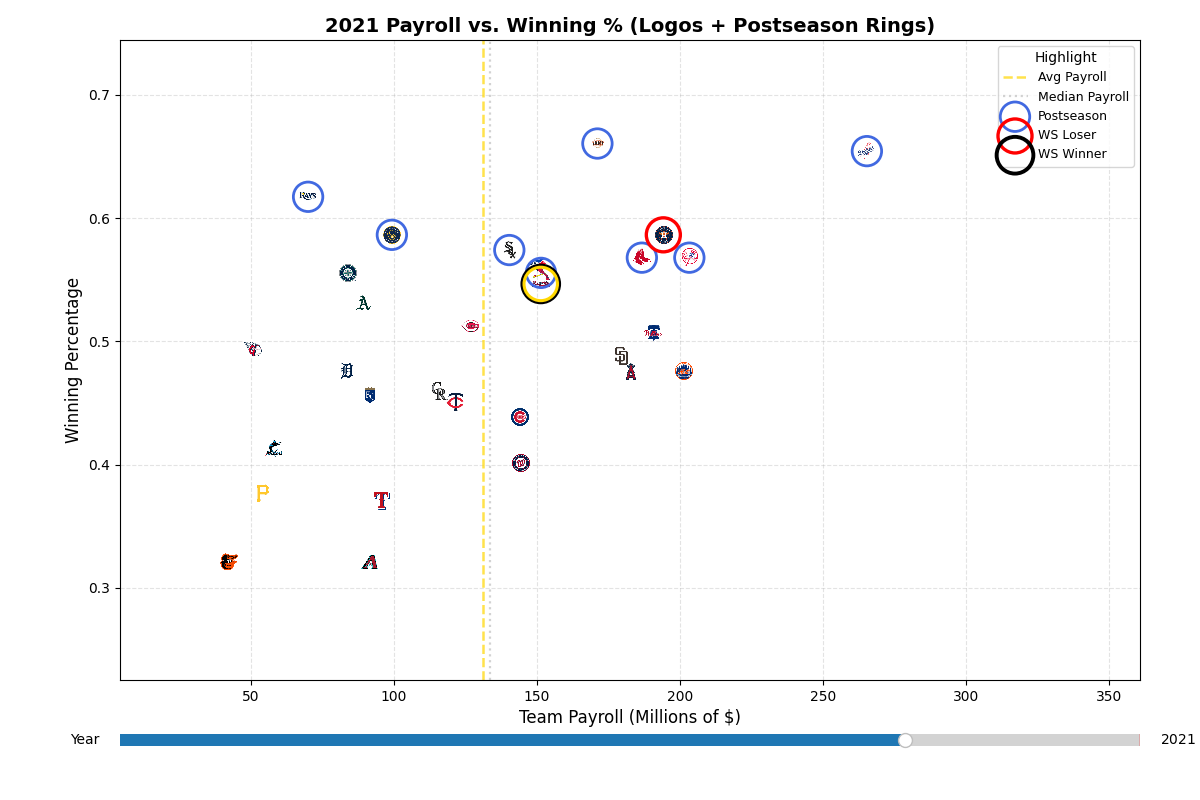

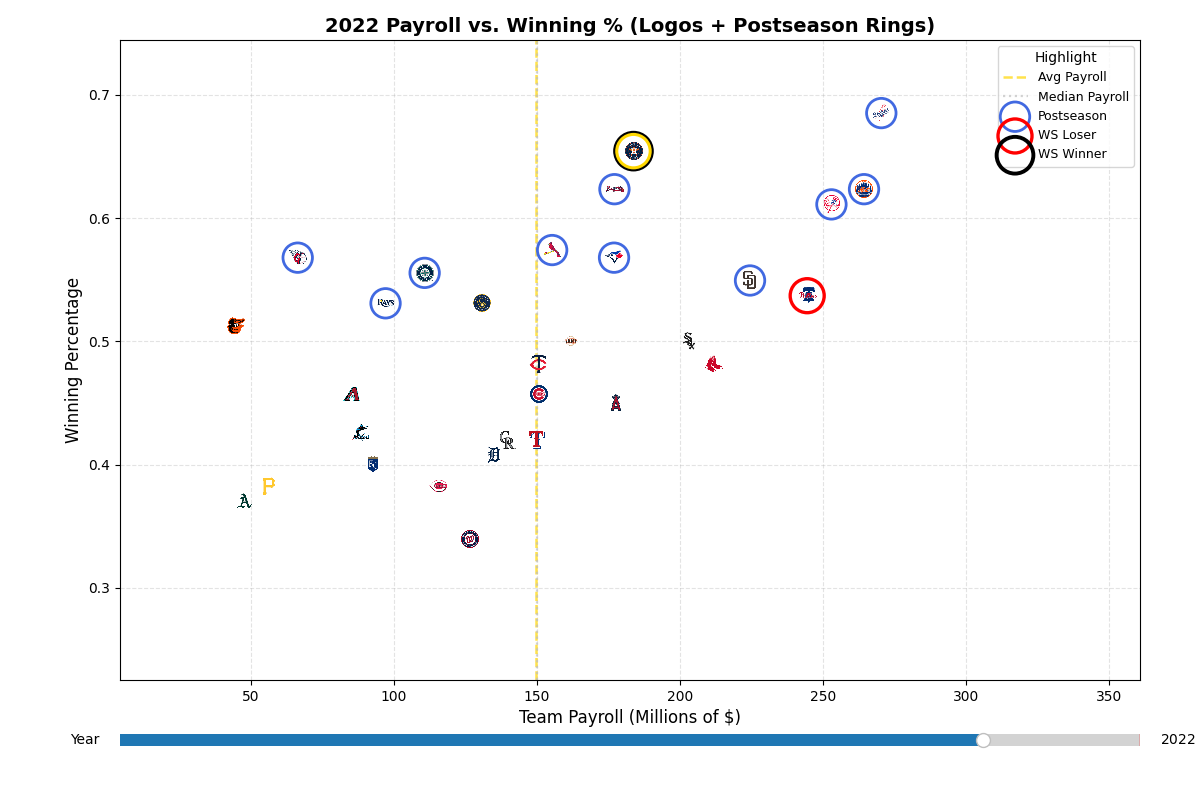

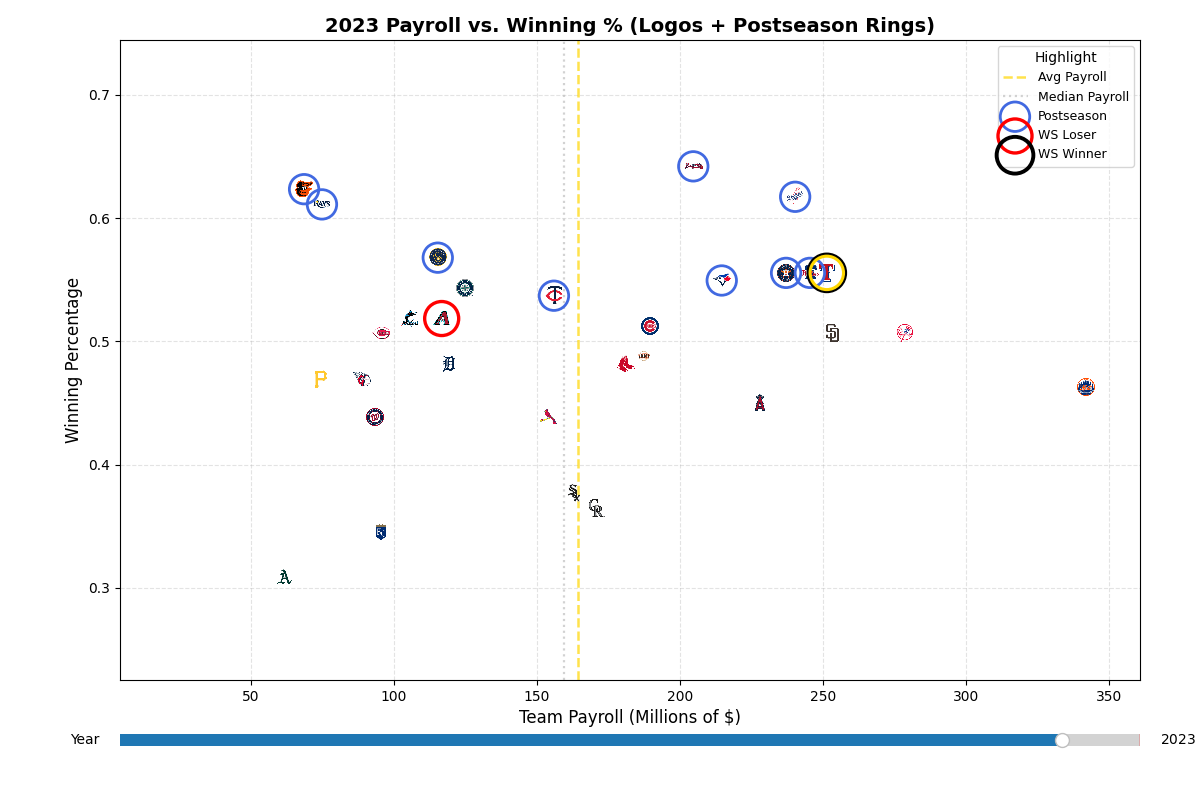

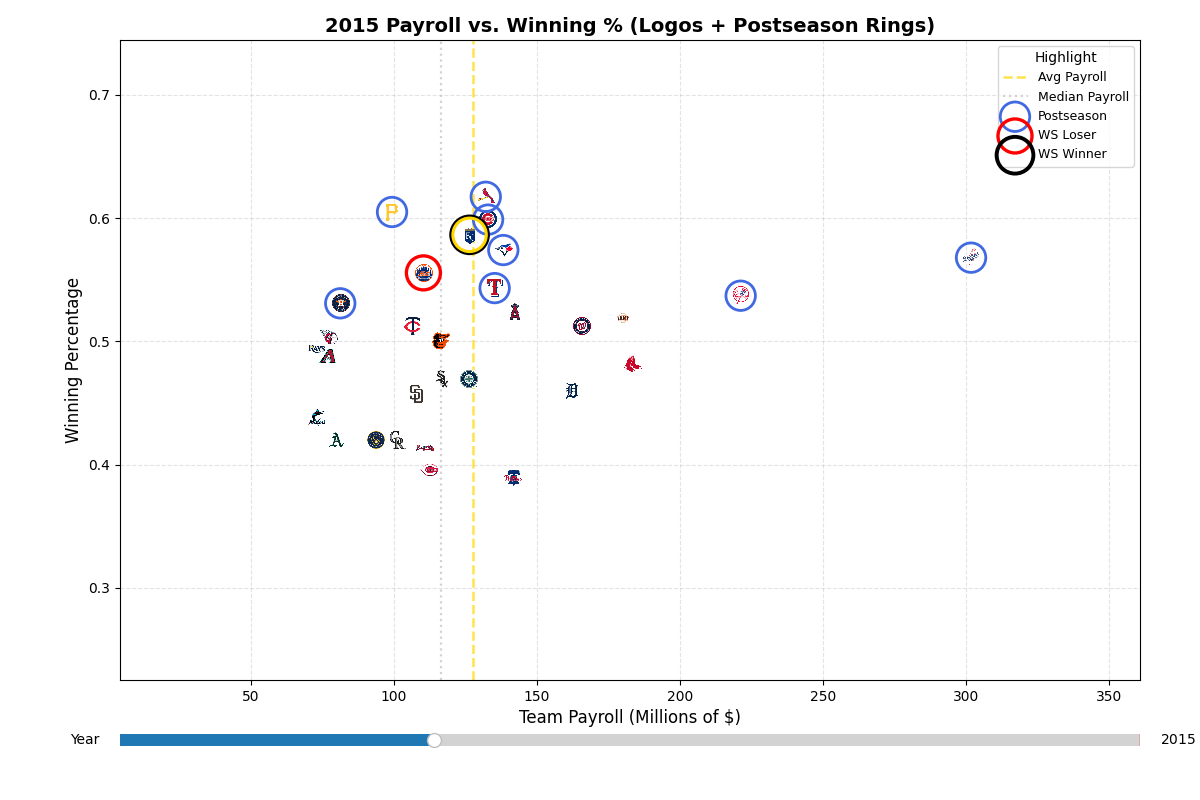

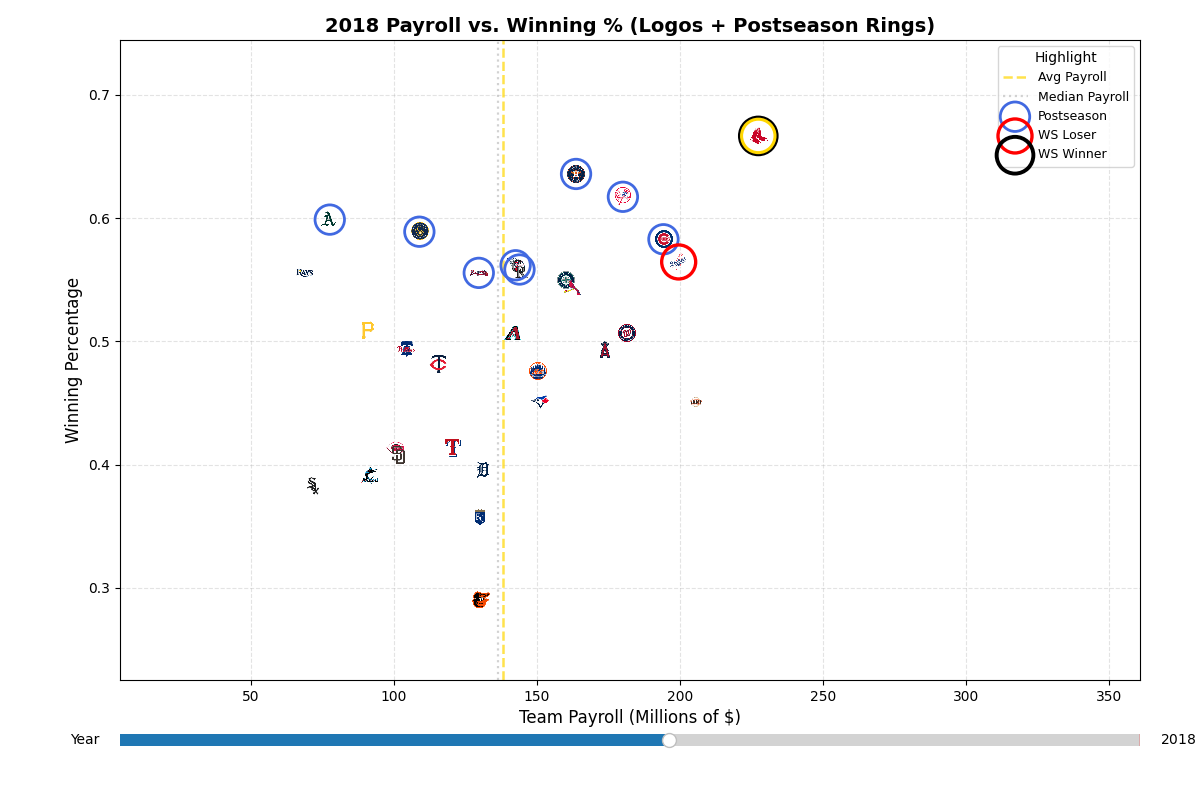

We could shorten the data set to 2018–2024 and prove an even stronger payroll–World Series participation relationship - but 8 years is arguably too tight a frame to call it a structural trend on its own. 2011 - 2024 is a convenient data set - it's what was available readily. But it includes the mega-contracts of Albert Pujols and Alex Rodriguez, their $275 and $250 million contracts in 2011 now dwarfed by their 2020s counterparts, the $765 and $750 million deals of Shohei Ohtani and Juan Soto. The longer dataset includes the outlier year 2015, when both World Series participants—the Kansas City Royals and New York Mets—were below the annual average payroll. This is the only year in the data set that this anomaly occurred. Three seasons later, in 2018, the World Series between the Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Dodgers represented the first and third highest payrolls. This is the strongest relationship of payroll/World Series appearance in our data set, closely followed by the 2024 season when the fifth ranked Dodgers defeated the second ranked Yankees.

Since 2018 (excluding the shortened 2020 COVID season), only one of twelve World Series participants came from the bottom half of the league in payroll: the 2023 Arizona Diamondbacks. It’s not for lack of opportunity. In that span, twenty-two bottom-half payroll teams made the postseason—a 4.5% conversion rate from playoffs to World Series. Meanwhile, forty-three above-average payroll teams reached the postseason, and eleven advanced to the World Series, a 25.6% conversion rate. None of this guarantees anything, but it does narrow the path. Payroll doesn’t buy a parade; it buys probabilities, cushions injuries, and shortens the distance between a slump and a replacement.

The notion that money buys championships is too simplified for a sport where only 1 of 30 win a championship. But only 2 World Series winners since 2011 have come from below average payrolls, the most recent being the 2017 Astros - a team known to recent history more for their sign stealing than their frugality. Is there a future where small market/payroll teams win the World Series even 15% of the time - as they have since 2011? Or does 2018-2025 indicate a future baseball economy where payroll is a non-negotiable indicator of World Series championships?